Get to Know China: Your Complete Country Guide

China stands as one of the world’s most fascinating nations, blending ancient traditions with modern innovation. This comprehensive overview is perfect for students, travelers, business professionals, and anyone curious about this influential country.

You’ll discover China’s incredible journey from ancient civilizations through powerful imperial dynasties to today’s economic powerhouse. We’ll explore the country’s rich cultural heritage, from traditional practices that have survived thousands of years to the vibrant customs that define modern Chinese life. You’ll also get familiar with Beijing, China’s bustling capital that serves as both the political heart and cultural center of this vast nation.

From geographic features spanning deserts to mountains, national symbols that tell stories of pride and unity, to demographic insights about the world’s most populous country, this guide covers everything you need to understand China’s place on the world stage.

Ancient Civilizations and Imperial Dynasties

Early Chinese Dynasties and Their Revolutionary Contributions

The Shang Dynasty (c. 1600-1046 BCE) stands as China’s first historically confirmed dynasty, introducing groundbreaking innovations that would shape civilization for millennia. They developed the earliest known Chinese writing system using oracle bones, created sophisticated bronze-working techniques, and established complex urban centers. The Shang rulers perfected divination practices and implemented a hierarchical social structure that influenced Chinese society long after their fall.

The Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BCE) brought the revolutionary concept of the “Mandate of Heaven,” which justified dynastic rule through divine approval. This political philosophy became the cornerstone of Chinese imperial legitimacy. The Zhou period witnessed the flourishing of Chinese philosophy, with Confucius, Laozi, and other great thinkers emerging during the later Zhou era. Their administrative innovations, including the feudal system and detailed record-keeping, laid groundwork for future governmental structures.

During the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE), Emperor Qin Shi Huang unified China’s warring states and standardized currency, weights, measures, and writing systems. His reforms eliminated regional variations that had hindered trade and communication. The Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE) expanded these achievements, establishing the Silk Road trade networks and creating a merit-based civil service system through imperial examinations. Han innovations included paper, the compass, and advanced metallurgy techniques that spread throughout the ancient world.

The Great Wall Construction and Strategic Military Defense

The Great Wall represents one of humanity’s most ambitious construction projects, stretching over 13,000 miles across northern China. Built primarily during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), the wall incorporated and expanded earlier defensive structures created by various warring states. Construction required millions of workers, including soldiers, peasants, and prisoners, with an estimated death toll reaching hundreds of thousands.

The wall’s design reflects sophisticated military engineering principles. Watch towers positioned at strategic intervals allowed for rapid communication through smoke signals and beacon fires. The wall’s height and thickness varied based on terrain and threat levels, with some sections reaching 25 feet tall and 20 feet wide. Interior passages allowed troops to move quickly along the wall’s length, while outer walls featured crenellations for archer protection.

Beyond its defensive function, the Great Wall served as a customs barrier controlling trade along the Silk Road. Guards collected taxes on goods passing through designated gates, generating substantial revenue for imperial coffers. The wall also facilitated communication across vast distances, with messages traveling from one end to the other in just days through the relay system.

Imperial Systems That Shaped Modern Governance

Chinese imperial administration created lasting governmental structures that influence modern Chinese politics. The emperor sat at the apex of a complex bureaucracy, supported by the Mandate of Heaven doctrine that legitimized dynastic rule. Below the emperor, a sophisticated hierarchy of officials managed provinces, prefectures, and counties, creating administrative consistency across vast territories.

The civil service examination system, refined during the Tang Dynasty (618-907), democratized government service by selecting officials based on merit rather than birth. These exams tested candidates on classical literature, poetry, and administrative skills, creating a educated bureaucratic class. This meritocratic approach contrasted sharply with European feudalism and influenced modern competitive examination systems worldwide.

Imperial legal codes, particularly the Tang Code, provided detailed regulations covering criminal law, administrative procedures, and social relationships. These codes balanced Confucian moral principles with Legalist emphasis on strict punishment. The concept of collective responsibility, where families and communities answered for individual crimes, reinforced social stability while maintaining order across diverse populations.

Key Historical Figures Who Transformed the Nation

Emperor Qin Shi Huang revolutionized Chinese civilization through unprecedented unification efforts. He abolished feudalism, standardized currency and measurements, and connected existing walls into the Great Wall. His book burning campaigns and persecution of scholars remain controversial, but his administrative reforms created the foundation for imperial China’s longevity.

Confucius (551-479 BCE) developed philosophical principles that guided Chinese society for over two millennia. His emphasis on social harmony, filial piety, and moral governance shaped imperial administration and family structures. Confucian ideals influenced education, law, and social relationships throughout East Asia.

Emperor Wu of Han expanded Chinese territory dramatically, establishing protectorates in Central Asia and opening trade routes to the West. His military campaigns secured the Silk Road, while his domestic policies strengthened central authority and promoted cultural exchange. Wu’s reign marked the beginning of China’s emergence as a major world power.

Empress Wu Zetian became China’s only female emperor, ruling during the Tang Dynasty’s golden age. She promoted meritocracy, expanded the civil service system, and fostered religious tolerance. Her successful reign challenged traditional gender roles and demonstrated effective female leadership in imperial China.

Rich Cultural Heritage and Traditional Practices

Philosophical Foundations of Confucianism and Taoism

China’s philosophical landscape rests on two towering pillars that have shaped the nation’s worldview for over two millennia. Confucianism, founded by Kong Qiu (Confucius) in the 6th century BCE, emphasizes social harmony through proper relationships, respect for authority, and moral cultivation. The philosophy centers on key concepts like ren (benevolence), li (ritual propriety), and junzi (the exemplary person). These ideas permeate Chinese society today, influencing everything from family dynamics to business practices.

Taoism, attributed to Laozi, offers a contrasting yet complementary perspective. This philosophy celebrates the natural order and encourages followers to live in harmony with the Tao (the Way). Core principles include wu wei (effortless action), balance between opposing forces (yin and yang), and the pursuit of simplicity. While Confucianism governs social behavior, Taoism provides spiritual and personal guidance.

These philosophies don’t compete but rather create a balanced framework for Chinese thought. Many Chinese people seamlessly blend Confucian ethics in their public lives with Taoist principles in their personal spiritual practice. This philosophical duality explains China’s ability to maintain social cohesion while embracing individual spiritual exploration, creating a unique cultural foundation that continues to influence modern Chinese society.

Traditional Arts, Calligraphy, and Literature

Chinese artistic expression represents one of humanity’s longest continuous cultural traditions, spanning over 4,000 years. Calligraphy stands as the most revered art form, considered the purest expression of Chinese aesthetics. Master calligraphers dedicate decades to perfecting their brushwork, creating pieces that capture both meaning and beauty. The four treasures of the study—brush, ink, paper, and inkstone—remain essential tools for practitioners who view calligraphy as meditation in motion.

Traditional Chinese painting, closely linked to calligraphy, emphasizes capturing the spirit rather than exact physical appearance. Artists use techniques like:

- Gongbi: Detailed, precise brushwork with rich colors

- Xieyi: Freehand style focusing on capturing essence

- Shan shui: Landscape painting representing harmony between humans and nature

Chinese literature boasts masterpieces that continue captivating readers worldwide. The Four Great Classical Novels—Journey to the West, Water Margin, Romance of the Three Kingdoms, and Dream of the Red Chamber—showcase storytelling brilliance that influenced countless generations. Poetry reached extraordinary heights during the Tang Dynasty, with masters like Li Bai and Du Fu creating works that remain central to Chinese education.

These artistic traditions aren’t museum pieces but living practices. Modern Chinese artists still train in classical techniques, while contemporary literature builds on ancient narrative structures, ensuring cultural continuity.

Festivals and Celebrations That Unite Communities

Chinese festivals create powerful bonds that transcend geographical and generational boundaries, serving as vibrant expressions of shared identity. The Spring Festival (Chinese New Year) stands as the most significant celebration, drawing hundreds of millions of Chinese people home for family reunions. This massive migration, known as chunyun, represents the world’s largest annual human movement. Families gather for elaborate feasts, exchange red envelopes filled with money, and participate in traditions like setting off fireworks to ward off evil spirits.

The Mid-Autumn Festival celebrates harvest time and family unity, with people gathering to admire the full moon while sharing mooncakes—dense, sweet pastries filled with lotus seed paste, egg yolks, or other delicacies. This festival embodies the Chinese value of completeness and togetherness, as the round moon symbolizes family reunion.

Other major celebrations include:

| Festival | Season | Key Activities |

|---|---|---|

| Dragon Boat Festival | Summer | Racing dragon boats, eating zongzi |

| Qingming Festival | Spring | Honoring ancestors, tomb sweeping |

| Lantern Festival | Winter | Lighting lanterns, solving riddles |

| Double Ninth Festival | Autumn | Climbing mountains, respecting elders |

These celebrations maintain their power because they combine ancient spiritual beliefs with practical social functions. They provide structured opportunities for families to reconnect, communities to bond, and cultural knowledge to pass between generations. Even as China modernizes rapidly, these festivals remain central to Chinese identity, adapting to contemporary life while preserving their essential character.

Beijing as the Political and Cultural Center

Historical Significance as the Imperial Capital

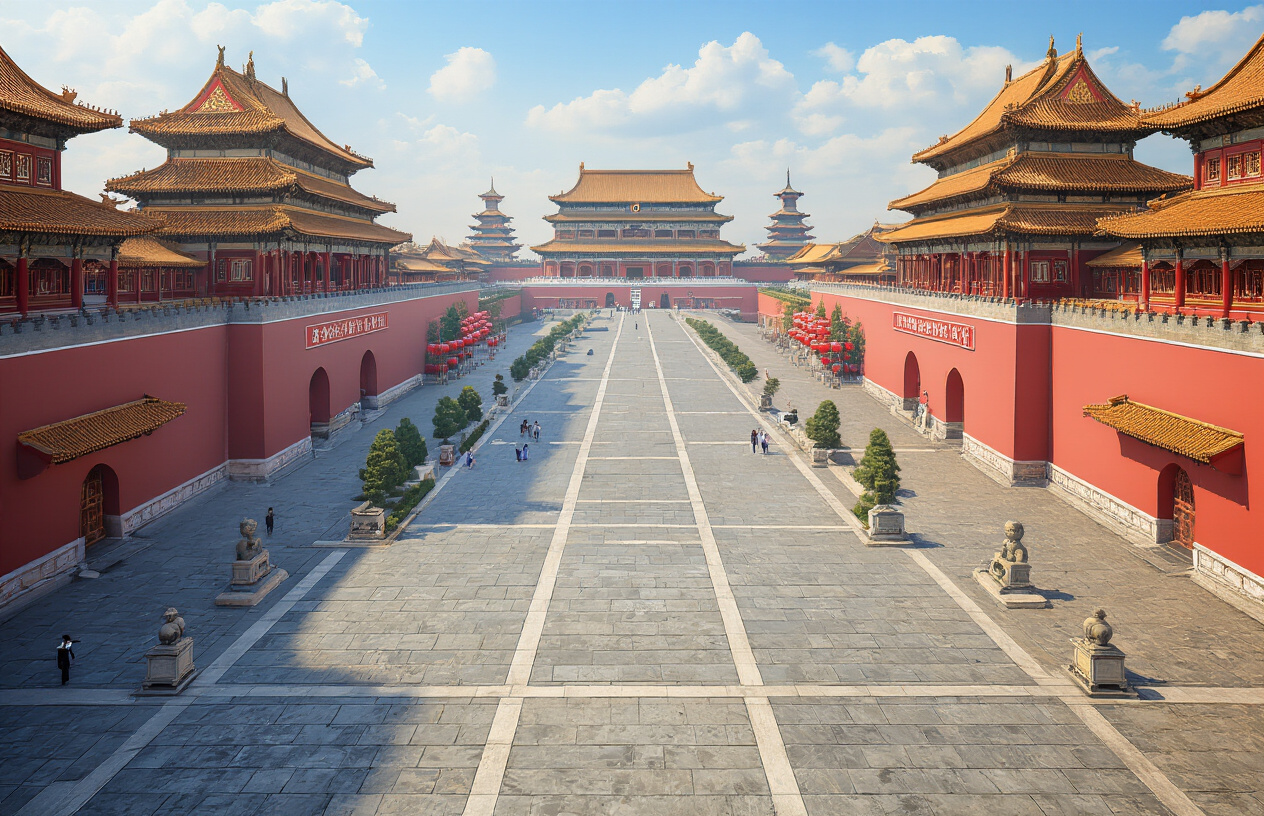

Beijing has served as China’s capital for over 800 years, earning its status as one of the world’s most historically significant political centers. The city first became a capital during the Jin dynasty in 1153, but reached its greatest prominence under the Yuan dynasty when Kublai Khan established it as his imperial seat in 1271. The Ming dynasty solidified Beijing’s role as the imperial capital in 1421, when Emperor Yonglo moved the court from Nanjing and began construction of the magnificent Forbidden City.

The strategic location of Beijing made it an ideal choice for imperial rulers. Positioned near the northern frontier, it provided direct oversight of the Great Wall defenses while remaining connected to the empire’s heartland through the Grand Canal system. The city’s layout reflects traditional Chinese cosmological principles, with the Forbidden City at its center representing the emperor’s divine mandate to rule under heaven.

Throughout different dynasties, Beijing accumulated layers of imperial architecture, ceremonial sites, and administrative buildings that transformed it into a living museum of Chinese imperial history. The city’s design follows feng shui principles and traditional urban planning concepts that emphasize harmony between human settlement and natural forces.

Modern Infrastructure and Urban Development

Today’s Beijing showcases remarkable urban transformation while preserving its historical character. The city spans over 16,400 square kilometers and houses more than 21 million residents, making it one of the world’s largest metropolitan areas. Modern Beijing features an extensive subway system with over 400 stations across 27 lines, connecting every corner of this massive urban sprawl.

The 2008 Summer Olympics catalyzed significant infrastructure improvements, including the construction of iconic venues like the Bird’s Nest Stadium and the Water Cube. These projects demonstrated Beijing’s capacity to blend cutting-edge architecture with traditional Chinese design elements. The city’s skyline now combines ancient temples and traditional hutongs with gleaming skyscrapers and modern commercial districts.

Beijing’s ring road system organizes traffic flow in concentric circles around the historical city center. The Central Business District (CBD) houses major corporations and international companies, while areas like Zhongguancun have become China’s equivalent of Silicon Valley, hosting numerous tech companies and research institutions.

Urban planners continue balancing modernization with heritage preservation, creating green spaces, pedestrian-friendly zones, and sustainable transportation options throughout the metropolitan area.

Key Landmarks and Tourist Attractions

The Forbidden City stands as Beijing’s crown jewel, representing the world’s largest palace complex with 980 surviving buildings spread across 180 acres. This UNESCO World Heritage site attracts millions of visitors annually who come to explore its magnificent halls, courtyards, and imperial collections spanning six centuries.

Tiananmen Square, the world’s largest public square, serves as Beijing’s ceremonial heart and can accommodate over one million people during major gatherings. The square houses important monuments including the Monument to the People’s Heroes and Chairman Mao’s Mausoleum, making it a focal point for both tourists and political ceremonies.

The Temple of Heaven represents a masterpiece of Ming dynasty architecture where emperors performed annual ceremonies to ensure good harvests. Its unique circular buildings and intricate wooden construction demonstrate advanced engineering techniques and deep cultural symbolism.

Other essential attractions include:

- Summer Palace: Imperial garden featuring Kunming Lake and traditional pavilions

- Hutongs: Traditional narrow alleys showcasing authentic Beijing neighborhood life

- Great Wall of China: Multiple sections accessible from Beijing, including Badaling and Mutianyu

- Lama Temple: Active Tibetan Buddhist monastery with stunning architecture

- Beijing National Stadium: Iconic “Bird’s Nest” from the 2008 Olympics

Government Institutions and Administrative Functions

Beijing serves as the seat of the Chinese government, housing all major political institutions within the city’s boundaries. Zhongnanhai, a former imperial garden adjacent to the Forbidden City, functions as the central headquarters for China’s top leadership and decision-making bodies.

The Great Hall of the People, located on the western side of Tiananmen Square, hosts the National People’s Congress and serves as the venue for major state functions and international diplomatic meetings. This massive building can accommodate over 10,000 delegates and features state-of-the-art facilities for legislative sessions.

The city houses numerous ministries, government agencies, and state-owned enterprises that coordinate national policies across China’s vast territory. Foreign embassies and diplomatic missions maintain their presence in designated embassy districts, facilitating international relations and trade agreements.

Beijing’s administrative structure operates at multiple levels, from the municipal government overseeing city-wide policies to district-level offices managing local community services. This hierarchical system enables efficient governance of one of the world’s most populous urban areas.

Cultural Sites and Museums

The National Museum of China ranks among the world’s most visited museums, displaying artifacts spanning 5,000 years of Chinese civilization. Located on the eastern side of Tiananmen Square, it houses over 1.4 million cultural relics including ancient bronzes, ceramics, calligraphy, and paintings that tell the story of Chinese cultural development.

The Palace Museum, housed within the Forbidden City, contains the world’s largest collection of Chinese art and antiquities. Its treasures include imperial porcelain, jade artifacts, ancient scrolls, and royal furnishings that provide intimate glimpses into imperial court life.

Beijing’s cultural landscape extends beyond museums to include active performance venues like the National Centre for the Performing Arts, nicknamed “The Egg” for its distinctive oval design. This architectural marvel hosts opera, ballet, concerts, and theatrical performances that blend traditional Chinese arts with contemporary international productions.

Traditional cultural sites dot the city, including Confucius Temple, where scholars have honored the great philosopher for over 700 years. The Beijing Opera, recognized as UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage, continues performing at venues throughout the city, preserving this unique art form that combines music, drama, acrobatics, and elaborate costumes.

Geographic Features and Territorial Overview

Vast Landscape Diversity from Mountains to Plains

China’s geography reads like nature’s greatest hits collection. The country spans an incredible 9.6 million square kilometers, making it the world’s third-largest nation by land area. This massive territory contains practically every type of landscape you can imagine.

The western regions showcase some of Earth’s most dramatic scenery. The Himalayas tower along the southwestern border, home to Mount Everest’s northern face. Moving east, the Tibetan Plateau stretches across a quarter of China’s territory, sitting at an average elevation of 4,500 meters above sea level. This “Roof of the World” gives way to the Gobi Desert in the north and the Taklamakan Desert in the northwest, creating some of the planet’s most challenging environments.

Central China tells a different story entirely. Here, fertile plains and rolling hills dominate the landscape. The North China Plain, formed by centuries of sediment deposits, creates some of Asia’s most productive farmland. The Loess Plateau, covered in wind-blown yellow soil, has supported agriculture for thousands of years despite its challenging terrain.

Eastern China presents yet another face, with coastal plains meeting the Pacific Ocean across more than 14,000 kilometers of coastline. River deltas create incredibly fertile growing regions, while mountain ranges like the Qinling Mountains serve as natural barriers between northern and southern China, influencing everything from climate patterns to cultural development.

Major Rivers and Their Economic Importance

China’s river systems function as the country’s economic arteries, carrying both water and wealth across the continent. Three major rivers dominate this network, each playing unique roles in the nation’s development.

The Yangtze River, stretching 6,300 kilometers from the Tibetan Plateau to the East China Sea, ranks as Asia’s longest river and the world’s third-longest. This waterway supports nearly 400 million people along its banks and generates roughly 40% of China’s GDP. The Three Gorges Dam, completed in 2012, represents one of humanity’s most ambitious engineering projects, providing hydroelectric power while controlling devastating floods that historically plagued the region.

The Yellow River earned its nickname from the massive amounts of loess sediment it carries, giving the water a distinctive yellowish color. Though shorter than the Yangtze at 5,464 kilometers, this river holds special significance as the cradle of Chinese civilization. Ancient settlements along its banks grew into some of history’s first major cities.

The Pearl River system in southern China connects Hong Kong, Macau, and Guangzhou, creating one of the world’s most economically productive river deltas. This network supports the Pearl River Delta Economic Zone, home to over 120 million people and serving as China’s manufacturing heartland.

These rivers provide irrigation for agriculture, transportation routes for goods, hydroelectric power generation, and fresh water for hundreds of millions of people.

Climate Zones and Regional Variations

China’s enormous size creates a climate puzzle with six distinct zones, each supporting different lifestyles and economic activities. This diversity means that while northern cities experience harsh winters with temperatures dropping to -40°C, southern tropical regions maintain warm weather year-round.

The northeast experiences a harsh continental climate with long, bitter winters and short, warm summers. This region, known as Manchuria, sees snow covering the ground for up to six months annually. Despite the challenging conditions, the area produces significant amounts of soybeans, corn, and wheat during its brief growing season.

Northern China, including Beijing, deals with a continental monsoon climate featuring hot, humid summers and cold, dry winters. The region receives most of its annual precipitation between June and September, creating distinct wet and dry seasons that have shaped agricultural practices for millennia.

Central and southern China enjoy a subtropical monsoon climate with abundant rainfall and longer growing seasons. The Yangtze River valley benefits from this climate, supporting rice cultivation and dense population centers. Summers bring intense heat and humidity, while winters remain relatively mild.

The far south experiences a tropical monsoon climate, with Hainan Island maintaining temperatures above 20°C throughout the year. This region supports tropical agriculture, including rubber plantations and exotic fruit cultivation.

Western China presents the most extreme variations, from the frigid Tibetan Plateau to the scorching Taklamakan Desert, where temperatures can swing 40 degrees between day and night.

National Symbols and Their Meaning

Five-Star Red Flag Design and Symbolism

The People’s Republic of China’s flag features a bold red background with five yellow stars positioned in the upper left corner. The design carries deep meaning rooted in Chinese political ideology and historical struggle. The red field represents the communist revolution and the blood shed by martyrs who fought for China’s liberation from imperial rule and foreign occupation.

The five stars create a distinctive pattern that tells China’s political story. The large star symbolizes the Communist Party of China, while the four smaller stars represent the four main social classes that Chairman Mao identified as the foundation of the new socialist state: the working class, the peasantry, the urban petite bourgeoisie, and the national bourgeoisie. Each smaller star points toward the larger one, illustrating unity under Party leadership.

The flag’s proportions follow specific guidelines, with the design occupying exactly one-quarter of the flag’s area. The yellow color of the stars contrasts sharply with the red background, ensuring visibility and symbolic clarity. This color combination also reflects traditional Chinese aesthetics, where red and gold represent prosperity, good fortune, and imperial dignity.

Designer Zeng Liansong, a citizen from Wenzhou, created this winning design among thousands of submissions in 1949. His concept beat elaborate alternatives that included geographic elements like the Yellow River, demonstrating how simple, powerful symbolism can capture national identity more effectively than complex imagery.

National Anthem and Cultural Significance

“March of the Volunteers” serves as China’s national anthem, originally composed as a rallying cry during the war against Japanese invasion in the 1930s. Nie Er wrote the music while Tian Han penned the lyrics, creating a piece that would become one of the world’s most recognizable national songs. The anthem’s martial tempo and urgent lyrics reflect China’s historical struggles and determination to defend sovereignty.

The song gained popularity through the 1935 film “Children of Troubled Times,” where it appeared as a theme song. During World War II, Chinese resistance fighters adopted it as an unofficial anthem, and its emotional power helped unite people across different regions and social backgrounds. The lyrics call citizens to “arise” and “march on,” using language that emphasizes collective action and national defense.

After 1949, the Communist government officially designated “March of the Volunteers” as the national anthem, though political changes during the Cultural Revolution led to temporary lyrical modifications. The original version was restored in 1978, recognizing its historical authenticity and emotional resonance with the Chinese people.

The anthem plays during important state ceremonies, international sporting events, and daily flag-raising ceremonies in schools across China. Its melody remains instantly recognizable to Chinese citizens worldwide, serving as a musical symbol of national pride and shared identity that transcends political differences and generational gaps.

Official Emblems and State Representations

China’s national emblem combines traditional Chinese architectural elements with modern political symbolism. The central image features Tiananmen Gate, the historic entrance to Beijing’s Forbidden City, surrounded by golden wheat stalks and a mechanical gear. This design represents the alliance between China’s agricultural heritage and industrial modernization goals.

Above Tiananmen Gate, five yellow stars mirror the flag’s design, reinforcing the Communist Party’s central role in governance. The wheat stalks symbolize agriculture and the peasant class, while the gear represents industry and the working class. Red ribbons tie these elements together, echoing the flag’s revolutionary symbolism and creating visual unity across China’s official symbols.

The emblem appears on government buildings, official documents, currency, and diplomatic materials worldwide. Its circular design follows feng shui principles while incorporating Western heraldic traditions, creating a symbol that communicates both to domestic and international audiences.

Regional variations of official symbols exist throughout China’s provinces and autonomous regions, but all incorporate elements that connect to the national emblem. These adaptations allow local identity expression while maintaining clear links to central authority, reflecting China’s approach to balancing unity with diversity across its vast territory and multiple ethnic groups.

Demographic Composition and Population Dynamics

Population Size and Growth Trends

China stands as the world’s most populous nation with approximately 1.41 billion people, though this number has been shifting dramatically in recent years. The country experienced explosive population growth throughout the 20th century, but this trajectory changed course around 2022 when China’s population began declining for the first time in decades. The fertility rate has dropped to just 1.09 children per woman, well below the replacement level of 2.1.

The one-child policy, implemented from 1979 to 2015, significantly shaped China’s demographic landscape. While successful in controlling rapid population growth, it created lasting consequences including an aging population and gender imbalances. The government has since introduced policies encouraging families to have more children, including the two-child policy in 2015 and the three-child policy in 2021, but cultural and economic factors continue to keep birth rates low.

Population density varies dramatically across the country, with eastern coastal regions supporting hundreds of people per square kilometer while vast western territories remain sparsely populated. The Hu Huanyong Line, an imaginary diagonal line drawn across China, illustrates this stark divide – roughly 94% of the population lives southeast of this line on just 43% of the land.

Ethnic Diversity and Minority Groups

China officially recognizes 56 distinct ethnic groups, making it one of the world’s most ethnically diverse nations. The Han Chinese constitute approximately 91.6% of the population, while the remaining 55 minority groups account for about 8.4%, totaling over 114 million people.

The largest minority groups include:

- Zhuang (16.9 million) – primarily in Guangxi region

- Hui (10.6 million) – Muslim Chinese scattered throughout the country

- Manchu (10.4 million) – descendants of the Qing Dynasty rulers

- Uyghur (10.1 million) – Turkic-speaking people in Xinjiang

- Miao (9.4 million) – spread across southern China

- Yi (8.7 million) – mainly in Yunnan and Sichuan provinces

China has established five autonomous regions specifically for minority populations: Xinjiang, Tibet, Inner Mongolia, Guangxi, and Ningxia. These areas enjoy certain cultural and linguistic protections, though integration policies have sometimes created tensions. The government promotes unity among all ethnic groups while attempting to preserve cultural diversity through various programs and preferential policies in education and employment.

Urbanization Patterns and Migration

China’s urbanization represents one of the largest human migrations in history. The urban population has skyrocketed from 18% in 1978 to over 64% today, with projections suggesting it could reach 75% by 2030. This massive shift has transformed the country’s social and economic landscape.

Major urban clusters dominate the demographic map:

| Urban Cluster | Population | Key Cities |

|---|---|---|

| Pearl River Delta | 86 million | Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Hong Kong |

| Yangtze River Delta | 130 million | Shanghai, Nanjing, Hangzhou |

| Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei | 110 million | Beijing, Tianjin, Shijiazhuang |

Internal migration has created a floating population of over 280 million people who have moved from rural areas to cities for work. These migrant workers often face challenges accessing urban services due to the hukou (household registration) system, which ties social benefits to one’s place of birth. Recent reforms have begun addressing these inequalities, allowing easier urban registration and access to healthcare and education.

Age Distribution and Social Demographics

China faces a rapidly aging population that presents both opportunities and challenges. The median age has risen to 38.4 years, and by 2050, nearly 330 million people will be over 65 – about 26% of the population. This demographic shift stems from decades of low fertility rates and increasing life expectancy, now at 78.2 years.

The age structure reveals significant imbalances:

- 0-14 years: 17.95% (declining youth population)

- 15-64 years: 70.35% (working-age population)

- 65+ years: 11.70% (rapidly growing elderly population)

Gender ratios remain skewed due to historical preferences for male children during the one-child policy era. Currently, there are about 105 males for every 100 females, creating challenges in marriage markets and family formation. Educational attainment has improved dramatically, with literacy rates reaching 96.8%, and women now represent over half of university graduates. Life expectancy gaps between urban and rural populations are narrowing, though disparities in healthcare access persist across different regions and income levels.

Economic Powerhouse and Global Trade Leader

Manufacturing Hub and Export Capabilities

China stands as the world’s factory floor, producing everything from smartphones to solar panels. The country manufactures about 28% of global goods, making it the largest manufacturing economy worldwide. Chinese factories churn out products for major international brands, taking advantage of efficient supply chains, skilled labor forces, and massive production scales that keep costs competitive.

The export machine runs on impressive infrastructure – massive ports like Shanghai and Shenzhen handle containers bound for every corner of the globe. China exports over $3.7 trillion worth of goods annually, including electronics, machinery, textiles, and chemicals. The “Made in China” label appears on products in homes and businesses across six continents.

Manufacturing clusters have developed around specific industries. Guangdong Province dominates electronics production, while Zhejiang focuses on textiles and light manufacturing. These specialized regions create ecosystems where suppliers, manufacturers, and logistics providers work closely together, driving down costs and speeding up production times.

Technology Innovation and Digital Economy

The digital revolution has transformed China into a tech powerhouse that rivals Silicon Valley. Companies like Alibaba, Tencent, and ByteDance have built massive digital ecosystems serving billions of users. Mobile payments through WeChat Pay and Alipay have become so common that cash transactions seem almost obsolete in major cities.

China leads the world in several cutting-edge technologies. The country has more 5G base stations than the rest of the world combined and dominates electric vehicle production through companies like BYD and NIO. Artificial intelligence research centers in Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen compete with global tech hubs, while Chinese companies hold significant patents in areas like facial recognition and autonomous driving.

The government’s commitment to technological advancement shows through massive investments in research and development. State-backed venture capital funds support promising startups, while policies encourage collaboration between universities and private companies. This approach has created an innovation culture where new ideas can quickly scale to serve China’s enormous domestic market.

Agriculture and Food Production Systems

Feeding 1.4 billion people requires agricultural systems that operate at unprecedented scales. China produces more rice, wheat, and vegetables than any other country, using about 7% of the world’s arable land to feed nearly 20% of its population. Farmers have adopted modern techniques including precision agriculture, greenhouse cultivation, and genetic modification to maximize yields.

The agricultural sector employs roughly 25% of China’s workforce, though this percentage continues declining as people move to cities. Large agricultural cooperatives have replaced many small family farms, bringing mechanization and efficient resource management to rural areas. These cooperatives can negotiate better prices for seeds, fertilizers, and equipment while providing technical training to farmers.

Food security remains a national priority, driving investments in agricultural technology and sustainable farming practices. Vertical farming facilities in urban areas produce fresh vegetables year-round, while aquaculture operations make China the world’s largest fish producer. The government maintains strategic grain reserves and has established agricultural partnerships with countries across Africa and South America to secure long-term food supplies.

Financial Markets and Investment Opportunities

China’s financial sector has evolved rapidly from a centrally planned system to one of the world’s largest financial markets. The Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges combined represent over $10 trillion in market capitalization, while Chinese banks dominate global rankings by total assets. The yuan has gained international recognition, becoming the world’s fifth-most-used currency for international transactions.

Foreign investment flows into China through multiple channels. The Bond Connect and Stock Connect programs allow international investors to access Chinese securities markets directly. Meanwhile, China’s Belt and Road Initiative has created investment opportunities across Asia, Africa, and Europe as Chinese companies and financial institutions fund infrastructure projects worldwide.

Fintech innovation has revolutionized how people save, invest, and borrow money. Digital lending platforms serve millions of small businesses that traditional banks couldn’t reach efficiently. Robo-advisors manage investment portfolios for middle-class savers, while blockchain technology supports everything from supply chain financing to digital currency trials. These developments have made financial services more accessible while creating new investment opportunities across traditional and emerging sectors.

China stands as one of the world’s most fascinating nations, blending thousands of years of ancient wisdom with modern economic might. From the Great Wall built by imperial dynasties to today’s bustling megacities, the country has managed to preserve its rich cultural traditions while becoming a global economic powerhouse. Beijing serves as the heart of this massive nation, coordinating both political decisions and cultural preservation across diverse geographic regions that stretch from desert landscapes to tropical coastlines.

The numbers tell an impressive story – with over 1.4 billion people calling China home, it represents nearly one-fifth of humanity. This demographic strength, combined with rapid industrialization and strategic global trade partnerships, has transformed China into an economic giant that influences markets worldwide. Whether you’re interested in exploring ancient temples, understanding modern manufacturing, or simply appreciating the symbolism behind the red flag with five golden stars, China offers endless discoveries. Take time to learn more about this remarkable nation – its history, people, and growing global influence will likely shape our world for generations to come.